There once existed a dizzying array of special identity documents – called C.I. certificates – that were issued by the Canadian Government exclusively to its Chinese residents. These pieces of paper were intended to control, contain, monitor and even intimidate this one community.

C.I. certificates served many functions: identity documents; head tax receipts; and entry and exit authorization papers. The papers also were a constant reminder of a second-class status in Canada.

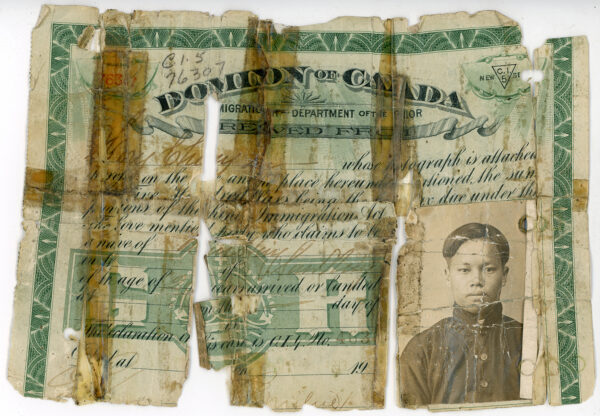

A Chinese immigrant in Canada would have to produce their papers on demand, and many carried their C.I. certificate with them at all times. Over the years, some certificates became worn, dog-eared and torn – a testament to how much these certificates were referred to in day-to-day activities.

C.I. certificates were coveted. To have one, meant a chance to earn a living and support a family back in China. And thousands of Chinese were forced to pay $500 just to have one with their name on it. Losing their C.I. certificate could create a host of problems and hours of interrogation trying to prove one’s identity.

Some people were forced to use their C.I. certificate as collateral to secure a private loan – handing the document over to the lender until the loan was paid off. On occasion, people sold off a C.I. certificate to help another immigrant enter the country as a “paper son or paper daughter.”

Despite how critical C.I. certificates were to survival, these documents were also despised – a constant reminder of how Chinese in Canada were a singled out and targeted for extraordinary, racially-bigoted treatment at the hands of government and the larger community

C.I.5. (1885 - 1911)

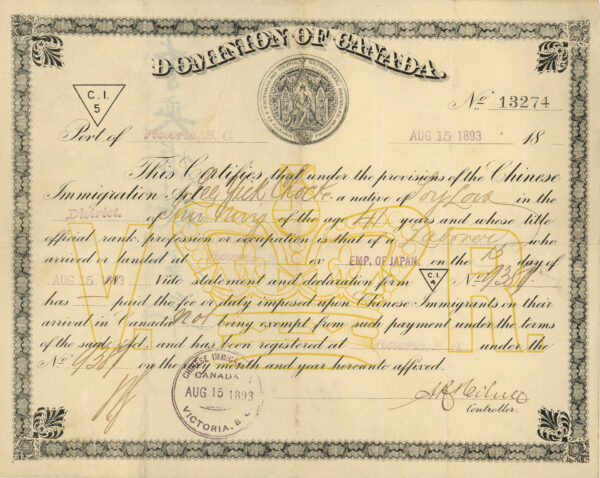

As the transcontinental railway was nearing completion in 1885, thanks to a large Chinese labour force in British Columbia, the first-ever “Chinese Head Tax” (aka entry fee) was introduced aimed exclusively at Chinese immigrants. The new legislation brought in to control Chinese immigration also spawned the first-ever entry document for Chinese called a C.I.5 certificate.

The ornate-looking C.I.5 document was issued to every Chinese immigrant, whether they were required to pay the head tax or not. (Merchants, diplomats, clergy, teachers and students remained exempt from the tax.)

A line buried deep in the certificate’s text was completed manually by an immigration officer and indicated whether or not the bearer paid the “fee or duty imposed on their arrival in Canada.”

This same certificate continued to be used as the head tax rate increased from its initial $50 (1885), to $100 (in 1900), and to its peak rate of $500 starting in 1903.

One challenge with this original C.I.5 design is that officials could not quickly identify the various classes of Chinese immigrants

C.I.9 (1910 - 1954)

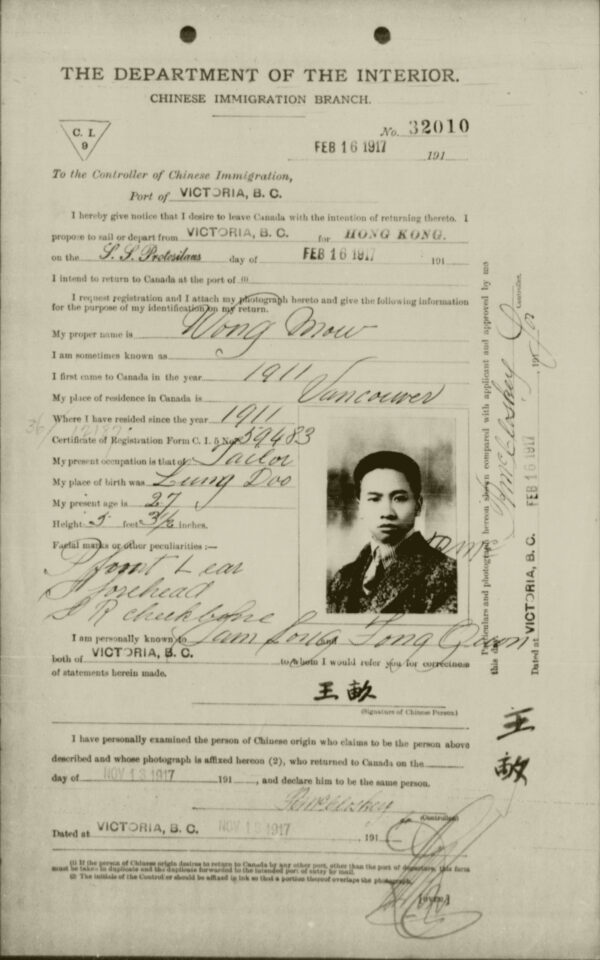

Starting in 1910, the federal government introduced the first travel-related C.I. certificate created exclusively for Chinese living in Canada. The purpose was to monitor travel in and out of the country.

A C.I.9 represented the first-ever mass use of photo identification in Canada. And the majority of photos attached to these certificates were taken by local photographers.

These C.I. certificates were issued both to Chinese who were immigrants, as well as Chinese born in Canada who wished to travel. Described as a form of “registering out” the document was only used for a temporary leave from Canada and was valid for a limited time period.

Every C.I.9 had to be returned when the traveler arrived back in Canada. Consequently, Library and Archives Canada has the complete collection and many have been scanned and are available for viewing online. (Some C.I.9s, such as those issued to foreign-born Chinese after 1920, are available only on microfiche at this time.)

Around 1912, the Government of Canada redesigned its basic C.I.5 certificate and also introduced a host of new C.I.s with different numbers and colours. All of them shared in common the requirement that a head and shoulders photo be attached to the document.

C.I.5 Revised (1912 - 1923)

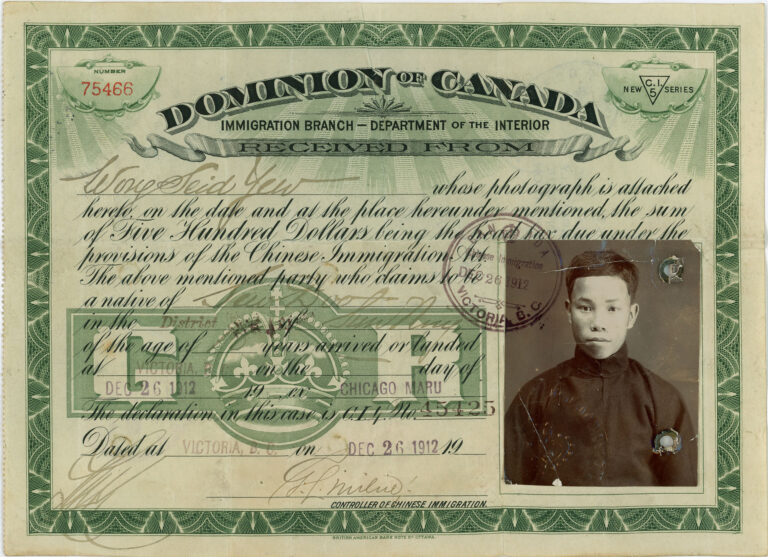

In 1912, a redesigned C.I.5 was now issued only to those who were required to pay the head tax. By then, the tax was $500, equivalent to two years of wages for the average Chinese living in Canada.

The certificate had a dark-green border and a portrait-style photograph was attached with a metal grommet.

This C.I.5 was not only an identity document and immigration landing certificate, it also served as an official receipt for payment of the head tax.

The photos on these certificates were generally taken in China and brought with the immigrant.

Only one original certificate was ever made and was held by the person to whom it was issued

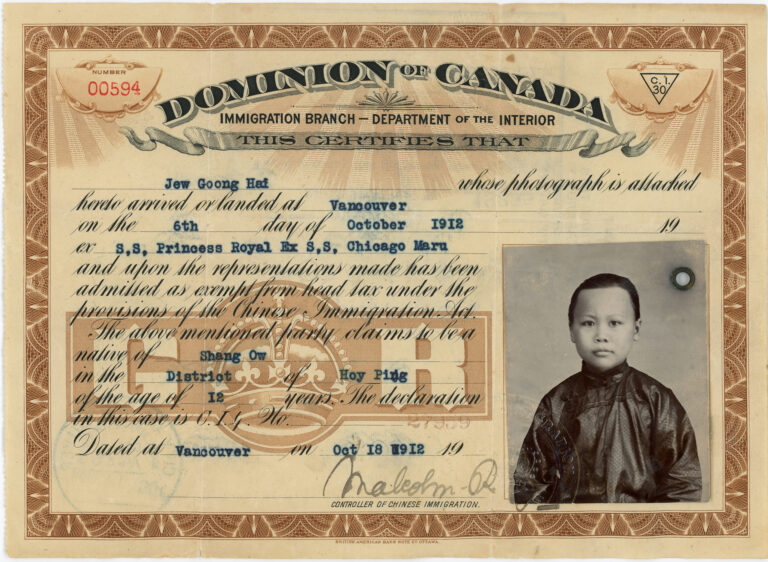

C.I.30 (1912)

After 1912, Chinese immigrants who were exempt from paying the head tax, were issued a C.I.30 when they arrived.

This certificate had a brown border with the photograph of the bearer.

Chinese who avoided the tax generally included those who claimed to be merchants, diplomats, clergy, scientists, teachers and temporary students. Since this class of immigrant avoided the astronomical entry fee, they were more likely to eventually bring over their wives and children from China, who were issued a C.I.30.

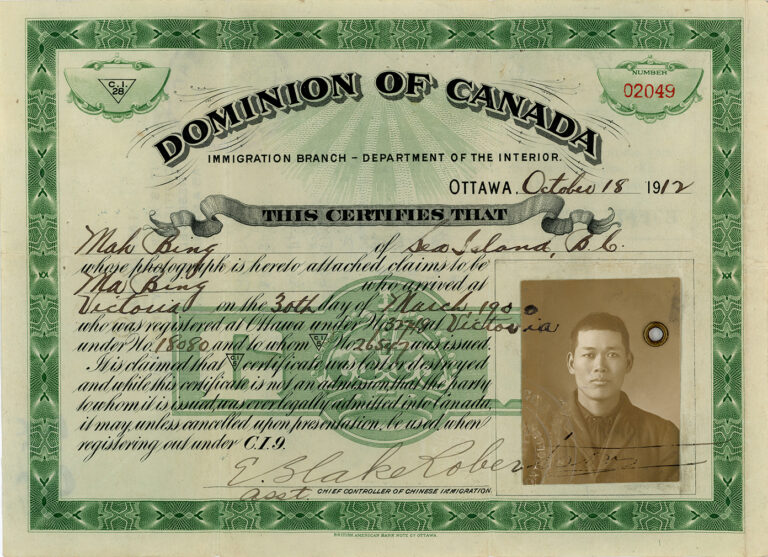

C.I.28 (1912)

If a Chinese person who had a C.I.5 claimed the certificate had been lost or destroyed or stolen, they were issued a “replacement certificate” called a C.I.28.

It was also green and contained the owner’s head and shoulders photograph. Since these were replacement documents issued in Canada, most of the photos on these certificates were taken by local photographers.

Buried within the text is information on the immigrant’s original date of arrival in Canada, and the serial number of their original C.I.5 certificate.

Only one original certificate was ever made and was held by the person to whom it was issued.

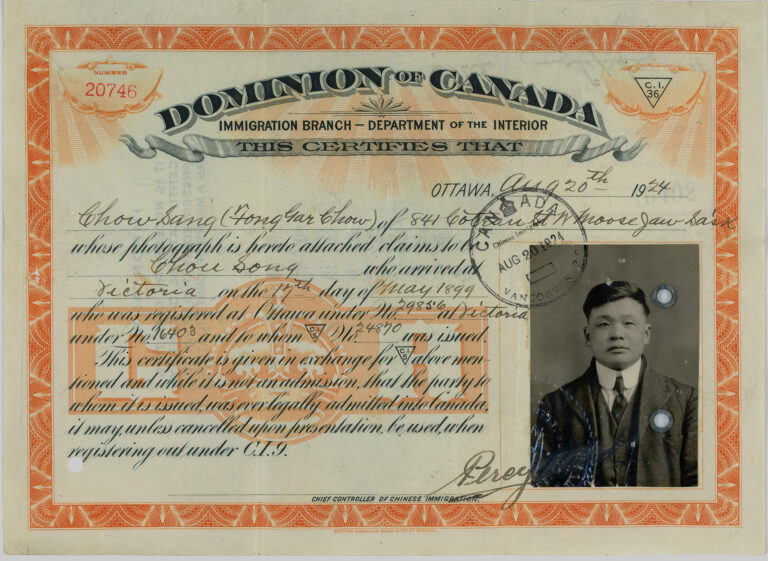

C.I.36 (1912)

Another replacement document was the C.I.36. It was issued to those Chinese who arrived before 1912 and thus were in possession of the original, photo-less C.I.5 certificate.

This certificate sported an orange border.

Buried within the text is information on the immigrant’s original date of arrival in Canada, and the serial number of their original C.I.5 certificate.

Many of C.I.36 certificates were issued in 1924, the year the Chinese Exclusion Act required that all Chinese in Canada had to register or re-register with the government.

Those who brought in their original, photo-less C.I.5 certificate were given this one as a replacement. Most of the photos on these certificates were taken by local photographers.

Only one original certificate was ever made and was held by the person to whom it was issued.

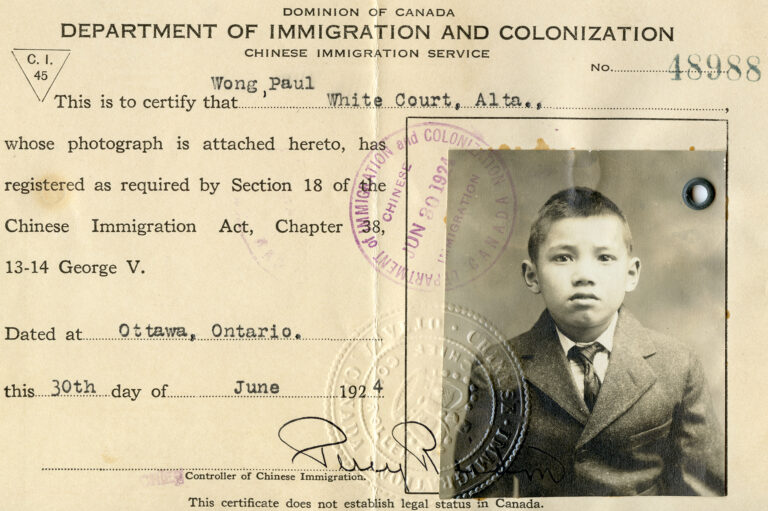

C.I.45 (1923)

When the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act came into effect, every Chinese person in Canada had one year to register (or re-register) with the government. Many Chinese brought in their C.I. certificate to be examined, recorded and stamped by immigration officials.

That system worked fine for the vast number of Chinese who had immigrated and had been issued a C.I. certificate when they landed. But what to do about the hundreds of Chinese who were born in Canada who did not have a C.I. certificate?

The C.I.45 certificate was the answer. Created in 1923 it was issued mainly to the first generation of Chinese born on Canadian soil.

Biege in colour and measuring about 7 x 5 inches, the C.I.45 was emblazoned with the title “Department of Immigration and Colonization.” Despite the fact that most of the children issued the card were born in Canada, at the bottom of each card was the text “This certificate does not confer any legal status in Canada.” That line became a sore point for a new generation of Chinese in Canada.

Only one original certificate was ever made and was held by the person or family to whom it was issued.

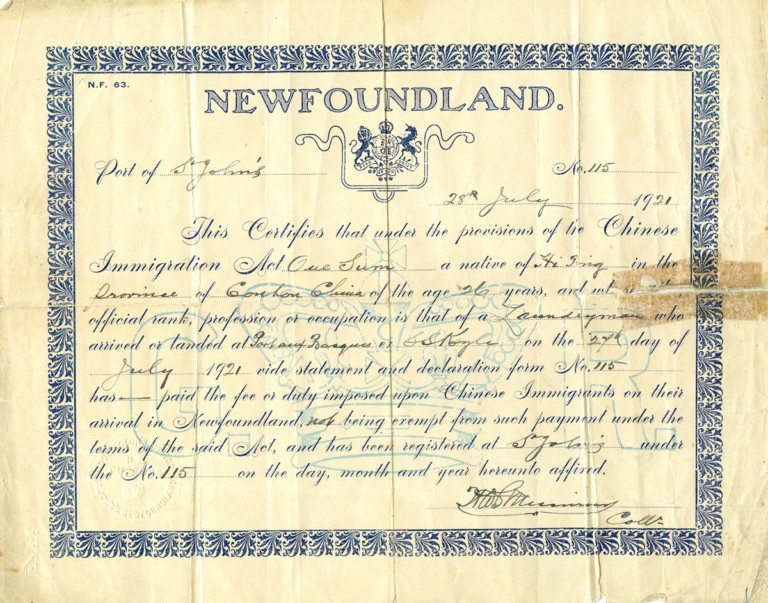

N.F. 63

Although not yet a part of Confederation in 1923, Newfoundland had its own head tax that it imposed on Chinese. From 1906 to 1949, any Chinese person who wanted to settle in Newfoundland or Labrador was forced to shell out $300. If admitted, the person was then issued this certificate, called a N.F. 63. More than 350 Chinese paid the head tax to the Newfoundland government.

Only one original certificate was ever made and was held by the person to whom it was issued.

Contact Us